A Map Of The Scale

Falling victim to a classic blunder!

I may start a new Bonus Round section called: “Spot the error in Michael’s previous post that he will now turn into a teachable moment”.

Yeah, maybe not. One of the charts (the “guitar neck” chart) contained an error.

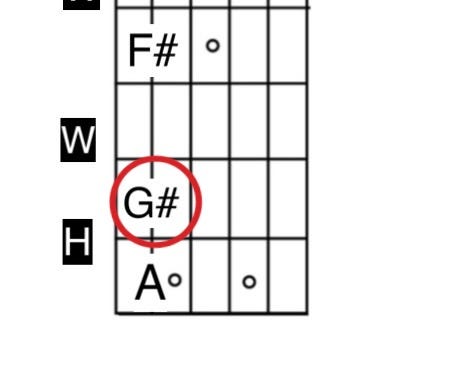

Yesterday’s version showed a “G”, not a G# (yes I corrected it for today). Is that a big deal? Yes and no. When demonstrating the correct notes for a Major scale using our WWHWWWH formula, yep, that’s a “Major” error (musician pun!). The interval between the 7th note of the scale (G# in this case) and the octave (A, since we were using an A Major scale) is a half step (that’s what the H indicates). When I missed the fact that I didn’t put the “#” after the G, I had actually made 2 errors. First, in this A Major scale there is a whole step between F# and G#, but without the # symbol it would be read in the language of music as a half step. Next, it’s a half step from G# to A, but when I left the # off, in the language of music, I had “said” something different: that it’s a whole step from the 7th note of a Major scale to the octave, when in fact the interval is a half step.

What if you were playing this note progression, rather than reading it? Would your band mates have said, “Hey, you violated the Iron Rule of only playing a Major 7th in a Major scale!” No, because there are few, if any, “Iron Rules” in playing music, at least the kind of playing we’re learning here (imagine the classically trained musicians clutching their pearls right now)! In fact, musicians play notes all the time that aren’t strictly in the scale and, depending on the piece, a minor 7th note there may have sounded kinda cool in context.

The lesson? When I’m demonstrating something for you, I should get it “right” in the context of the demonstration. If we’re playing music together, what’s “right” is whether it sounds good or not. “Good” in this case means “interesting”, because our ears hear interesting variations in music as, well, interesting!

So, on with today’s topic:

Music starts with a note. A group of notes arranged according to a traditional “formula” form a scale. The formula for a particular type of scale, in this case a Major scale, is an arrangement of notes in a particular order of “intervals” between notes. There are 2 basic kinds of intervals, the half step, and the whole step. Two half steps form a whole step, conversely, a whole step equals two half steps. What’s an interval in the form of a “step”, either half or whole? An interval is essentially the DIFFERENCE in the frequency of the waveforms of two different pitches of sound as perceived by our ears. A German physicist a long time ago laid the groundwork for the science behind the perception, and since his last name was Hertz, we use his name to describe the waveform frequencies we perceive as sounds. In music, we’ve described the frequency of the note we call “A” as 440 Hertz, written as 440Hz. Even that’s in some dispute, as an older description of the frequency of A is 433Hz, sparking all sorts of hubbub. For our purposes, there is a difference in the waveform frequency of sound between the note we describe as A and the note we describe as A#, and we call that difference a half-step interval. The difference between the frequency of A and the frequency of the note we call B is described as a whole step, with A# being halfway between A and B. To add to the confusion, the note we call A# (A sharp), is also called Bb (B flat). Same frequency, two names. Welcome to music theory! The difference in using A# or Bb as a name for that frequency is generally dependent on whether we’re using ascending pitches (# or sharps) or descending pitches (b or flats) in a group of notes.

So, notes form a scale: a group of notes (pitches) according to a theoretical formula of intervals described in terms of whole steps and half steps. For Major scales we start with a note, any note, and we call that not the “root” of the scale. It’s the place where the rest of the scale “grows” from, I suppose.

The formula is Whole, Whole, Half, Whole Whole, Whole, Half, and we can write it as WWHWWWH. Starting with the root, we ascend in pitches according to that formula. We often start on the note “C”, and there’s a really good reason for that. The C scale that results from applying the formula is unique because it has no sharp or flat notes, only what are called “Natural” notes (as opposed to sharp/flat notes, which are called “Accidentals”). The C scale then is C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and ends with the octave C note (an octave is a note pitched at a frequency exactly double the root pitch). The octave in a scale is important because it gives us a “place” to put the final interval of the scale.

On a piano, the C scale looks like this:

On the piano, the ivory (white) keys are natural notes, and the ebony (black) keys are accidentals. Because the unique C scale has no accidentals, it is played solely on the ivory keys. This gives us an easier way to see the intervals, and especially to visualize the two places in every scale where we have to use half steps. Notice between the E and F piano keys there is no ebony key. Likewise, between the B and C, no ebony key. That’s because there are no accidentals between E/F and B/C, so those intervals must be half steps. There is no B#/Cb, nor E#/Fb!

Every other scale has at least one accidental and one scale is all accidentals and no naturals!

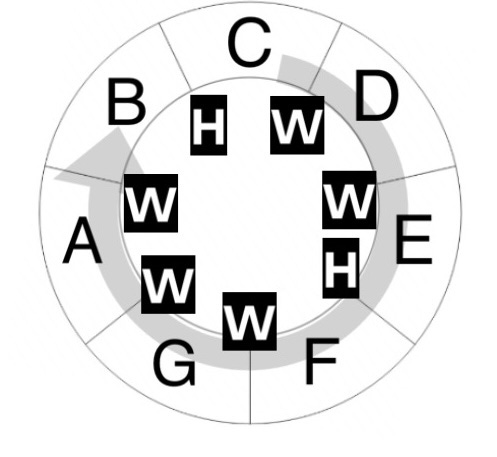

The piano chart shows the C scale in a linear fashion, but we can also visualize a scale in a circular fashion:

Same notes, same intervals, but here the root C note is also depicted as the octave C note, double the frequency of the root, but the same pitch relative to the other notes on the scale, and we need it to give context to the intervals. This circular depiction of the scale will be very helpful when we start building chords off of each of the notes in the scale. When the chords are built, the scale transforms into what we call a “key” in music. We’ll get there!

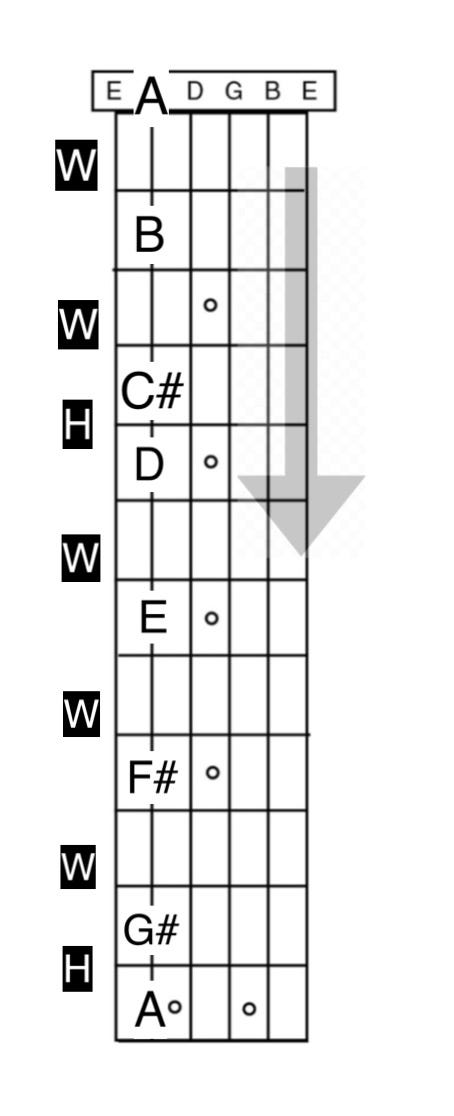

Because the guitar doesn’t have a C string as a root to build a scale from, I used the open A string to build a scale, the A Major scale. Something to ponder here is how there are 12 pitches between octaves, 7 “natural” notes, and 5 accidentals. Because every fret on the guitar is a half step relative to the frets immediately above and below, it takes 12 frets to get from the open (unfretted) tuning of the string to the octave, and most guitars have 2 inlays on that fret to denote visually that you’ve reached the octave. The little circles on the diagram correspond to the inlays on most guitar fretboards.

So that’s an AMajor scale, played on a guitar. Note it’s not the only AMajor scale available, you could start on the second fret of the G string and apply the same intervals. In fact you could start on any fret (as long as you had a total of 13 frets available before you reached the soundhole end of the fretboard) and with the same sequence of intervals, build a major scale rooted on the note you started from.

So, that’s a lot of music theory for one day!!

Next week we’ll expand on these principles and build chords to form a key from any scale. Then we’ll head back to some earlier newsletters in this series to revisit common chord progressions and which chords sound good and which might be somewhat discordant to our ears used to modern blues based music. Also, what the heck does that mean?!?!?

Yesterday’s Bonus Round answer:

The littering incident as described in the song Alice’s Restaurant was based on a real life situation. From the Wikipedia entry: “The arresting officer was Stockbridge police chief William J. Obanhein ("Officer Obie"), and the trial was presided over by Special Judge James E. Hannon.”

Bonus Round: Some of the “Classic Blunders” were described in the film “The Princess Bride”. Fortunately, the failure to sharp the 7th note in the Major scale was not actually included in the scene, though it probably ended up on the cutting room floor in post production. For next week: which absolutely fantastic musician, guitarist, vocalist and songwriter wrote the score for the Princess Bride?

Cheers, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic

I’m in “dire” need to know the answer!!