Yesterday’s Bonus Round: John Hurt - a true old time bluesman - one story is a record company exec dropped the nickname “Mississippi” on him, claiming the gimmick would sell more records. Mr. Hurt never liked it. People claimed he was one of the kindest, gentlest souls they had ever met. One of the greats!

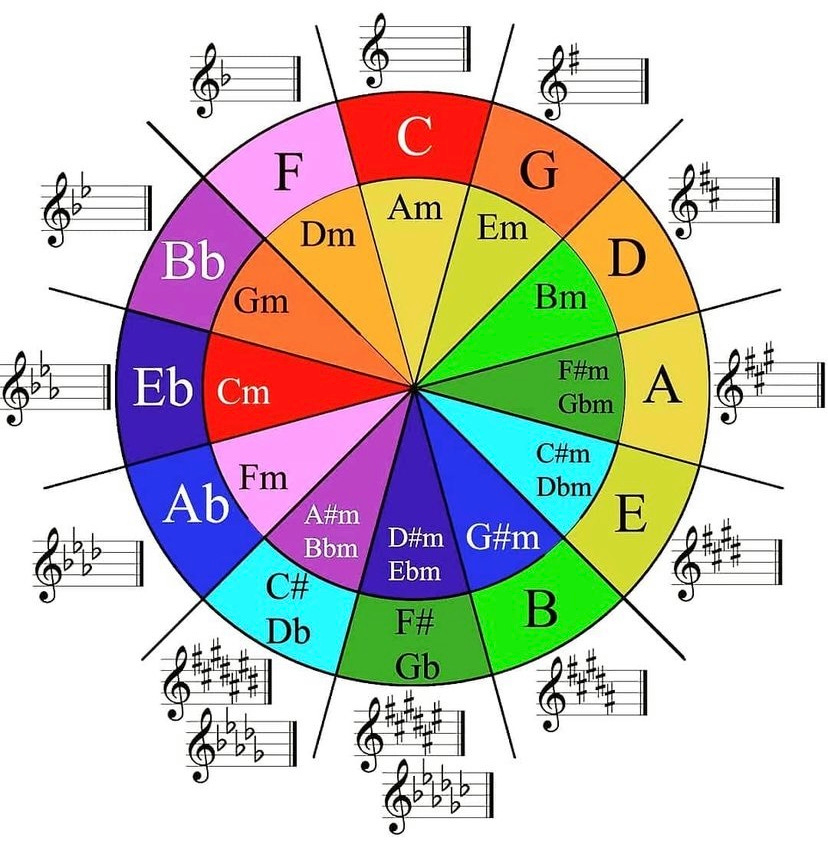

Today we’ll tidy up some loose ends and move along with some new ideas. Let’s take a quick look at the Circle of Fifths:

Here’s a more colorful chart that includes more key signature information in the outer ring than the one I previously used. Today I want to “decode” a little about this thing that makes it useful. Keep in mind there is much more here in terms of the math of musical interrelationships than I’m going into, but at this point much more would probably go too far into the theory side of things to be useful. First this is called the Circle of Fifths because each clockwise note is a fifth of the previous note. Example: G is the fifth note of the CMaj scale, so starting on C and going clockwise we see G. Building chords off of those 2 notes will give you the I and V chords in the Key of CMaj. If you go counterclockwise, the chart becomes a Circle of Fourths! In our example, the note in the counterclockwise direction is F, which is the fourth note of the C scale. Looking at both the notes to the left and right of any given note on the circle will give you the root notes of the IV chord and the V chord of the Key of the chosen starting note and you can quickly see the I-IV-V common chord progression of that key (CMaj- FMaj- GMaj in the Key of CMaj). Kinda handy for a quick look if you’re playing in an unfamiliar key. I’ve avoided the minor chord symbols in the inner ring so far because they serve several purposes, only one of which we’re going to talk about today. Continuing with the CMaj key example, the minor chord (Am) in the inner ring that corresponds with C, is the vi (minor vi chord, which can also be written as vi- , the dash being a somewhat superfluous, but handy, reminder it’s a minor chord) the chord symbol to the left is Dm, the ii- chord, the symbol to the right is the iii- chord Em, and finally, the chord to the right of that is noted as Bm. In reality, there’s no Bm chord diatonically in the the Key of CMaj, but there is a Bm° (Bmdim). Recall the vii chord of Major scales is a diminished chord, written as vii°. It’s a bit to remember, but if you need to transpose a chord chart on the fly because, for instance, the vocalist wants to sing in a key that better fits their vocal range, remember: start with the Major key you need the chords to, that’s the I chord, outer ring left is IV, right is V, inner ring left is ii-, directly below is vi-, right is iii-, and one more to the right is the diminished chord vii°. Practice with a few familiar Keys and you’ll pick up the pattern pretty quickly.

Ok, enough of that!! Moving on, we talked about how to count beats in measures with different notes. Here’s a great resource https://www.drumlessons.net/understanding-time/ (copyright DrumLessons.net) that explains counting way better than I can. It’s even more helpful because it gives you a little insight into the minds of drummers! Drummers are always your friend in the band, and the ones I know are also pretty funny peeps. The bass player is usually always listening to the drummer, and as you’re playing rhythm acoustic guitar, you should be checking in frequently with the drummer’s rhythm and tempo. Vocalists should too, more so if you’re both playing and singing, but vocalists can get a little busy at times with the audience and lyrical meter, so your rhythm and tempo and timing should always be in sync with the drummer in order to support the vocalist.

Finally, let’s introduce some ideas to complement the concepts of lyrical rhythm, meter and phrasing we talked about in previous posts. Whether you’re writing your own music, or creating your own unique take in covering someone else’s, those thing are important. If you’re writing your own stuff, and you intend to have lyrics with your music, as opposed to a strictly instrumental piece, or if you’re writing instrumental pieces you intend to write lyrics to later, those concepts take on more importance. I pretty much write lyrics and fit music around that, but I have admiration and perhaps more than a little envy for those who are capable of writing lyrics to existing instrumental music, either their own or in collaboration with someone else. In either case, a great starting point is the “hook”, either the lyric phrase that underpins and usually is repeated throughout the song, or a great riff that serves the same purpose.

In the upcoming weeks we’ll talk about how to capture those things, lyrical and musical hooks, that come to you inspirationally. Not everyone has that, and thank goodness, or there would be far too much great music out there to ever listen to!! On the other hand, you may have more inspirational potential than you give yourself credit for, and the only way to find out is by exploring, both lyrically and musically! I’ll give you some of my tips, and some resources to help you along the way!

Bonus Round: A pop/rock song with a 2 word lyrical hook about somebody’s mom!!

See you next week!!

Cheers, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic