Happy Thanksgiving, and some leftovers!!

Days of future passed…

Cleaning up a few things first this morning: a couple of weeks ago I asked in a bonus round for the name of the guitar style prevalent in Talking Blues songs, but spaced the answer. The style is called Piedmont or Southeastern Blues to distinguish it from other early forms of blues music, such as Mississippi Delta blues. Piedmont blues carried on the tradition of Ragtime, which was a popular music style in the late 1800s and through the turn of of the century. Ragtime is distinctive in it’s use of the vi (6) chord, often played as a Dominant 7 borrowed from another key. That may not make sense right now, but the key takeaway is that most modern blues based music (country, pop, rock, folk, Americana, and others) recognize the “rules” of music theory, and then break and ignore them as often as the result is interesting - and that’s quite often!!

Yesterdays Bonus Round: Paul Simon wrote “American Tune”, the story goes, because Richard Nixon had been re-elected President. It’s a great song, fun to play and sing, but as things turned out, a bit pessimistic about American resilience. The Concert In Central Park version with Art Garfunkel is is one my all time favorite songs.

So today, while we’re sort of winding down with the basics of music theory, it will still be a topic that winds through all we do as guitarists, singers, musicians, songwriters and recording artists and we’ll revisit theory often as we move to more practical applications

On that “note” (musician’s pun), let’s take a look at Triads in a little more depth before we move on to more exotic (and interesting!!) chord structures.

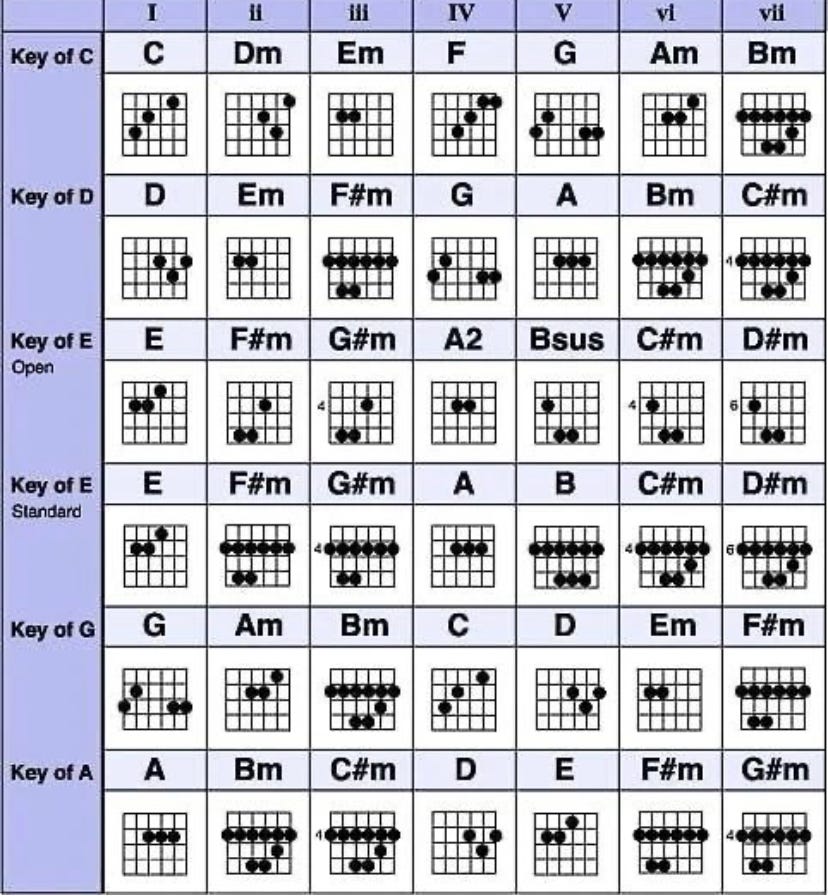

Reviewing: we start with a note, any note, of the 12 (7 naturals, 5 accidentals) and build a Major scale using the WWHWWWH formula. Then we take each note of the resulting scale, use each one as a root, and build a basic Triad chord from each note, using the M3,m3 (Major 3rd “below” a minor 3rd) structure for Major chords (the I, IV, and V), or the m3, M3 (minor 3rd “below” a Major 3rd) structure for minor chords (the ii, iii, and vi). We’ll leave the “diminished” chord, written as the vii° for now (the superscript “o”, which looks like a temperature symbol denotes a fully diminished chord - something we’ll talk about in future newsletters). We’re leaving that because almost no one uses it in modern blues based music, but true to form, if it is used, we almost always change it to a less dissonant form of the chord anyway.

If you’re trying to figure out what notes make up a basic chord, for instance while playing with others and and you want to play something that’s interesting and not quite native to the key (we call chords that aren’t strictly part of the key “non-diatonic”, also applies to notes used, but not strictly in the scale - notes and chords in the scale or key are called “diatonic”) you might want a quick way to calculate what’s diatonic, so you can change it to something non-diatonic that’s more interesting. “More interesting” often means adding/changing notes or chords to create musical “tension” - a sort of “something’s not quite right” feeling, that you then “resolve” by releasing the tension through going back to diatonic notes/chords. Cool to play, and the listener often finds the tension-release cycle interesting. Most modern blues based music involves tension and release all through the song, where the minors (ii, iii, vi) work together with the IV and V, to create tension, which then “resolves” to the I (the root, also called the “tonic”). Play a GMaj chord, followed by a CMaj chord and you’ll hear a common tension/release progression (the V- I).

In a future newsletter, I’ll include a chart of the notes in many common triads, until then if you want to work out some on the blank “scale” circle from last week’s post, feel free. If that’s daunting, you could use the somewhat embarrassing method I often use:

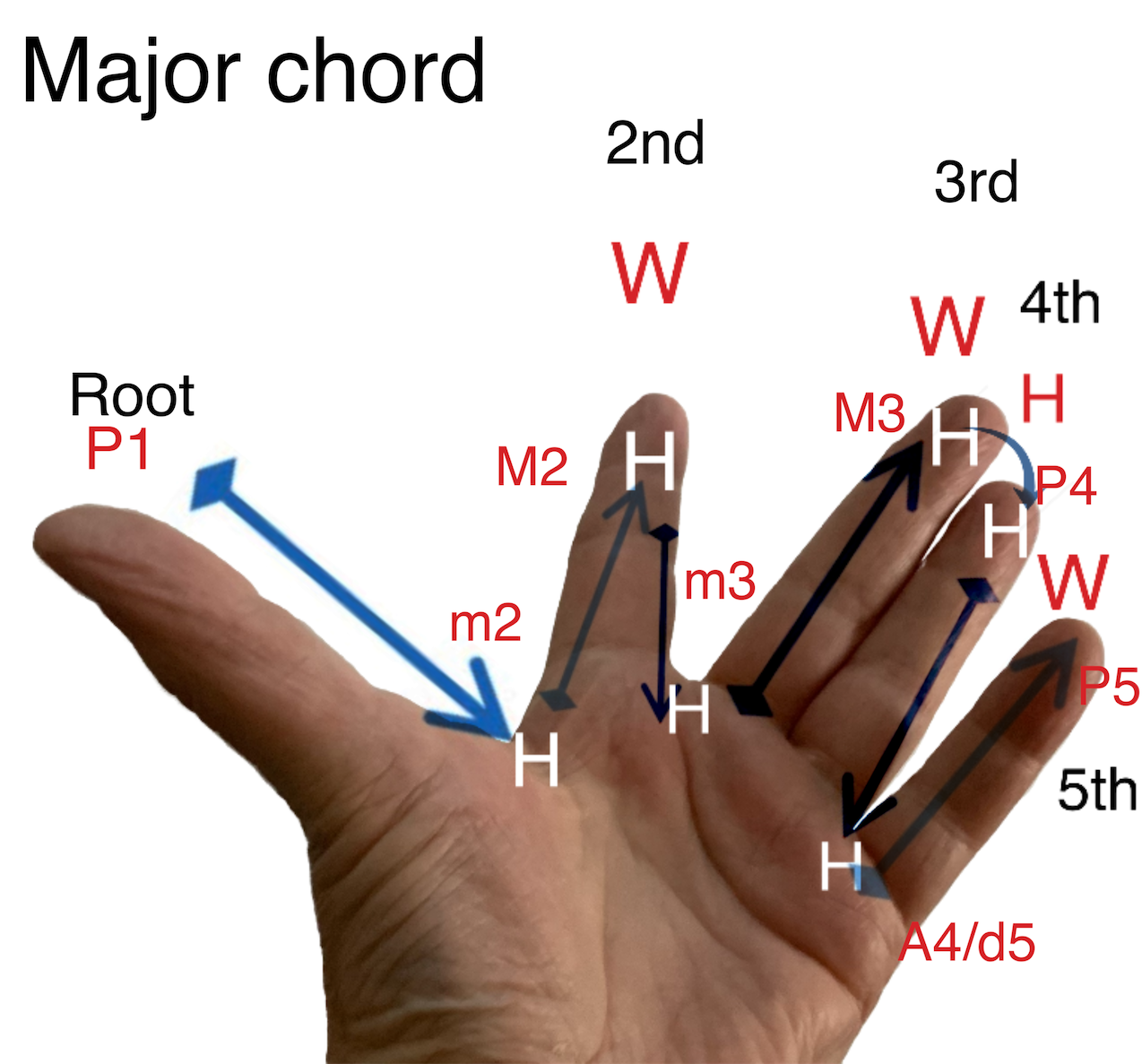

Yes, it’s my hand. I count notes of a triad on my hand. Kinda like kindergarten, but it works for me. Here’s how:

I use the tips of my thumb and fingers, and the spaces in between (webbing at the base of my thumb and fingers) to count half steps and whole steps. Like this for Major chord triads:

Remember to count accidentals between notes except between B and C, and E and F!

I’m counting the WWHW pattern for the first 5 notes of the scale, which lets me pick out the 1st (root), the Major 3rd and the Perfect 5th notes by the intervals that make up a Major chord. Like this, with intervals:

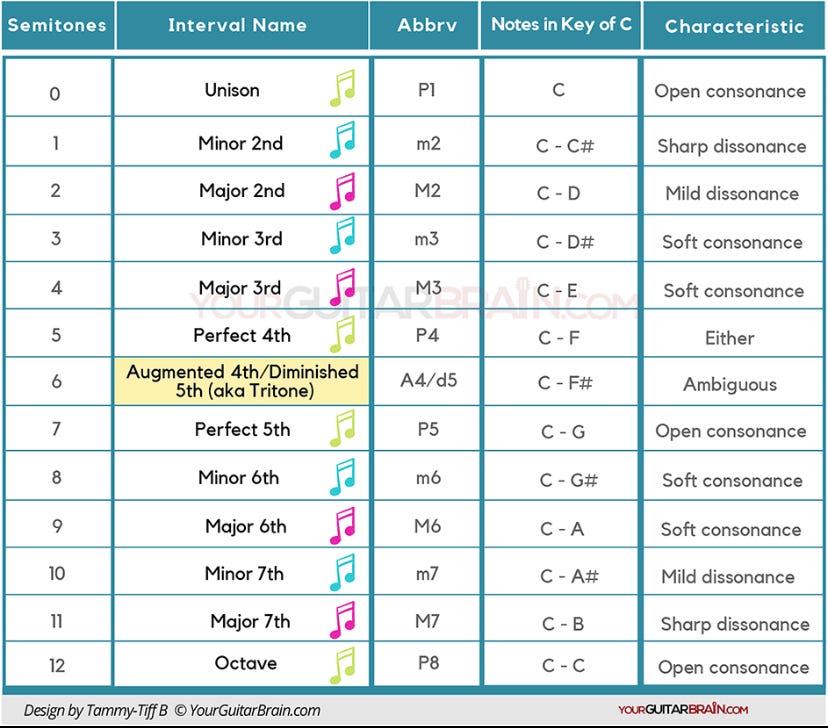

Note the A4/d5 interval between the Perfect 4th (P4) and the Perfect 5th (P5). Notes falling between Perfect intervals are called Augmented going “up” the scale in pitch, and diminished going “down” the scale in the pitch. The notes at the Perfect intervals are called Perfect because they are especially important in the tension/release resolutions. We’ll probably talk more about Perfects later (maybe not, it’s kinda esoteric), but for now, here’s a chart with the interval names:

Note the copyright by YourGuitarBrain.com. In this chart you see the semitones (another name for half steps) that conveniently line up with the fingertips and webbing counts on my hand. Also the names of the intervals with the Root note interval (zero - called Unison), 4th, 5th, and octave identified as Perfects. The example column uses the CMaj scale but includes the non-diatonic notes to illustrate half steps (semitones) of each interval, not from the previous note, but calculated from the root (tonic). Finally, the author gives a subjective impression of the quality of the tines at the intervals. Your mileage may vary.

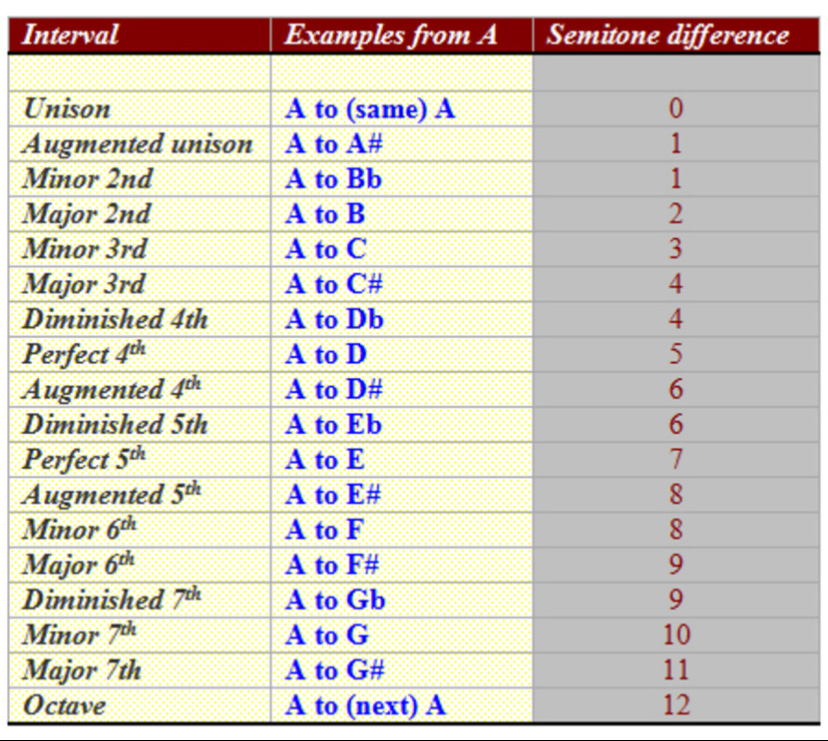

Here’s another chart with some slightly different names, apparently because everything in music theory has to have at least 2 or 3 different names!

Okay, this is pretty far down in the music theory weeds, but you’ll hear more than a few of these terms when playing with experienced musicians (though they’ll probably pretend they don’t count triads on their fingers,too!).

We still have a long way to go, especially when we get to chord extensions and chord voicings, but I’ll try to weave the theory into the practical. After the Thanksgiving holiday, I’ll relate a lot of this into the subject of a previous post, using a capo, and why it won’t be just for cheating with easy chords (though that’s always a plus!!).

Yesterday’s chart raised some questions:

The Roman numerals across the top as headers.

When we talk to other musicians we say things like, “Play the one, four, five”, or “A minor 2 would sound good after the 5”, meaning the chords in a key. Since we don’t have separate words for Roman numerals, when we write out what those verbal sentences mean, we use Roman numerals (helps to differentiate between notes in a scale). Since the (diatonic) order of chords in a Major key is Major (the root, also known as the tonic), minor (2 chord), minor (3 chord), Major (4 chord), Major (5 chord, also referred to as the “dominant”), minor (6 chord) and diminished (7 chord). We use upper case Roman numerals for Major chords (I, IV, V) and lower case for minor chords (ii, iii, vi), and a lower case with a symbol for the diminished 7 (vii°). The chart didn’t show diminished vii chords, probably because they’re most often played as minor chords of some type in modern music - note all the chords in the vii column are minors). As an aside, some musicians (notably jazz players) denote the minors even further (ii-, iii-, and vi-), possibly because jazz often uses only two notes of a chord, sometimes even just one, relying on our ears and surrounding chords to “fill in” the missing chord tones, which we as listeners pretty much do.

There are two examples of the key of EMaj and a couple of “different” chords in one of the examples, an “A2” and a “Bsus”. What the heck?

The first EMaj key shows the chords as they can be played “open”, meaning without using barre (bar) chords. A2 is shorthand for an “Asuspended2nd” chord, which could be written Asus2. Since there are two types of suspended chords, by convention, we use A2 as shorthand for Asuspended2nd, and Asus, or Asus4, to denote a suspended 4th chord. Suspended chords are chord voicings which are very interesting musically, but we’ll leave for another day.

What’s up with those 7 (vii) chords? As above, denoting minors in place of diminished because almost no one uses diminisheds anyway.

Bonus Round: Who performed the song suggested by the subtitle to yesterday’s post?

Bonus Bonus Round: Which fabulously popular band released an album with the name suggested by the subtitle to this post?

Thank you to all my subscribers (especially the new ones!!) and readers - this is such a blast for me!!! Please comment or ask questions in the comment section and I’ll respond in future posts!

Happy Thanksgiving, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic