So, some mea culpas to start off with. Yesterday’s capo conversion chart looked great. Right up until I pressed the “Publish” button, when some of the formatting decided to “play in a different key”. I corrected that, and if all goes according to SubStack’s support article, you should see a “Capo Conversion and Key Chart” box just above this paragraph. When I press the “read now” button, nothing happens for me, but maybe it will open after I publish this. If not, inside the box on the right is a smaller box with three lines. Pressing on that gives me a drop down menu with a “Download” option. You can download the PDF file, and print both the Capo Conversion chart and the Key Chart from yesterday’s post, properly formatted. Handy to take along to rehearsal if you need to change keys.

Yesterday’s Bonus Round was a bit of a train wreck, too. I-35 does not run through the city I thought it did, I was not doing well with Apple Maps yesterday. 🙃

So the subtitle clue was useless, but if you picked up on “Nashville”, as in the Nashville notation technique we’re going to talk about today, and the first thing you see is the Nashville skyline, you might have come up with “Nashville Skyline”.

“Nashville Skyline is the ninth studio album by American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, released on April 9, 1969, by Columbia Records as LP record, reel to reel tape and audio cassette. Building on the rustic style he experimented with on John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline displayed a complete immersion into country music. Along with the more basic lyrical themes, simple songwriting structures, and charming domestic feel, it introduced audiences to a radically new singing voice from Dylan, who had temporarily quit smoking—a soft, affected country croon.” - credit: Wikipedia.

A little bit further and you may even have come up with “Nashville Skyline Rag”, the sprightly, happy instrumental second cut on the album. A “rag” song is one in the ragtime style popular in the late 1800s through the early 20th century.

“Ragtime – also spelled rag-time or rag time – is a musical style that enjoyed its peak popularity between 1895 and 1919. Its cardinal trait is its syncopated or "ragged" rhythm. Ragtime was popularized during the early 20th century by ragtime composer Scott Joplin and his school of classical ragtime…” credit: Wikipedia.

Side note - lots of ragtime songs made considerable use of the vi- chord, it’s a sound still emphasized in “Piedmont blues” instrumental music, often heard accompanying the vocals in “Talking Blues” style songs such as Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant”. Though we use the vi- chord a lot in blues based pop, rock, country, and folk songs, it’s not emphasized to the same degree as in rag songs.

So, for today, we’re going to build on the idea of changing keys. Yesterday’s capo charts let you change chord shapes while remaining in the same original key by using the capo. Today, we’re going to change keys completely, and go from there.

Why would we change keys to a song we’ve already learned in the original key it was written in, and then maybe capoed to remain in that key, but playing with easier chord shapes? The answer is almost always because the vocalist wants to sing in a different key; one that suits their voice and vocal range. That could also be a temporary condition - a sore throat, dry conditions, any number of things. We’re there to support the vocalist, and changing keys, even on short notice, is one way we do that. If you are the vocalist for the performance, having bandmates that are willing to support you on a day when you just can’t pull off a high or low note in a certain key will be much appreciated. Having bandmates who can change keys and pull off a performance in minimal time is even better!!

One way to do that is by using “Nashville Notation”. It’s mostly specific to “chordal” instruments, that is, instruments that can play harmonies all at once, which is pretty much limited to those in the guitar and piano/keyboard families. Horn players or other wind instruments or strings (violin, viola, cello) play one note at a time (a melody), but several playing together can each play the separate notes of a chord, and they create a harmony. When guitarists strum across the strings, or pianists depress several combinations of keys with each hand, their instruments produce a harmony all at once. We rhythm guitarists do that when we play a chord “shape”. Lead guitarists will often play only one or two notes at a time as they riff, shred, and play licks up and down the fretboard. Experienced players who play lead guitar, or other non-chordal instrumentalists understand chords as a collection of notes, rather than a “shape” and some other notes besides the triad that forms the basic chord sound great when played “around” the chord. We’ll talk more about how we do that as well when we talk about chord “extensions” in future posts.

For today, lets think about a portion of yesterday’s capo chart.

I ii- iii- IV V vi- vii°

G: G Am Bm C D Em F#°

C: C Dm Em F G Am B°

D: D Em F#m G A Bm C#I’m using here what SubStack calls a “poetry block”, a pasted in block of text that I am assured will retain its original spacing. We’ll see after I hit “Publish”.

Written in Nashville notation, it would look like this:

1 2- 3- 4 5 6- 7°

G: G Am Bm C D Em F#°

C: C Dm Em F G Am B°

D: D Em F#m G A Bm C#Wow, Michael! Big change! Right? Looks simple enough, and in some ways it is, but this is a very simple Nashville notation. It is perhaps a little easier to read, just because the numerals aren’t being translated from Roman numerals as we look at it. The power of Nashville notation, though, is in the shorthand notations we can add to the numerals.

Let’s start at the beginning as we take a first look at Nashville notation. Where did it come from and why? Well, Nashville most likely, though there’s an equally good chance it originated elsewhere and gained wide adoption in Nashville because of the high concentration of session players (“hired guns”) there. It probably could have been called New York, Chicago, LA, or Memphis notation, or anywhere else session musicians, who need to adapt quickly on the fly to changes (or just flat improvise) were in recording studios supporting the “Names” who were prominent on the album cover. But, it ended up as Nashville notation, and that’s what we call it today.

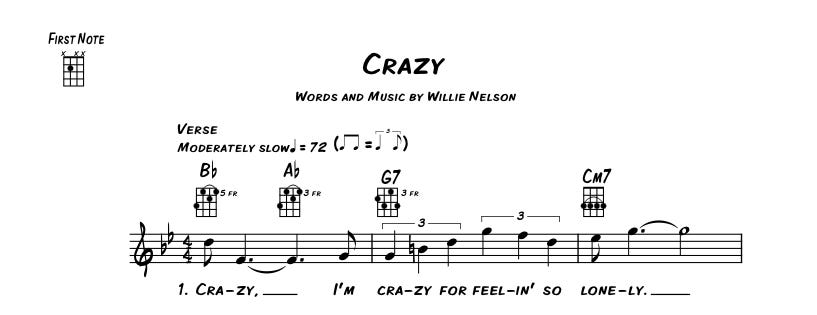

So that “power” in the added notation is real. We only see a bit of it in the example above though. Note the dash following the 2, 3 and 6 chords. They are the minor chords in the key. The “°” symbol denotes a diminished chord. Major chords stand alone until modified by further notation. Some of the added notation you might see in Nashville notations are kinda crazy, but we’ll talk more about how to do this (and there is a method!) in the coming weeks. For now, here’s a Nashville notation chart for Patsy Cline’s famous hit “Crazy”. Just like the song, this might seem a little, well, you’ll see…

Pretty complex. Unless you’re actually a session player, you’ll likely never see anything this “crazy”. It was probably created from what’s called a “lead sheet”. Lead sheets are sort of a hybrid chart with header and signature information, chords, score notation, and lyrics all in one. Because these are available for download for a fee from websites (this one is musicnotes.com), I’m only showing the first line for educational purposes. Usual disclaimer - I have no financial interest, but I have purchased lead sheets from musicnotes.com and other sites before.

Next week we’ll revisit our short “silly song” that we wrote from a throwaway line and set to music in the post from Feb 18 (find it in the (Archive) ).

Here’s a chord chart of our silly song, “Bad Timing”:

We’ll use this to make some quick header notes in order to quickly pen and ink a chord change, just like you might have to do in rehearsal.

Some links n’ stuff:

How to “write from the ‘hook’” tips:

Bonus Round: A crazy songwriter covers Paul Simon?

Cheers, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic