Off The Charts!!

The Dust In Kansas…

Today will be all about the charts: how they are useful, and how they’re not so useful.

A brief recap: the last few posts have been about music theory “lite”. The subject is vast, and the classical musicians are invested heavily in learning it all. Other musicians (notably the jazz crowd) take a lot of music theory, change some of the terminology, bend all the rules, and generally have a great deal of fun, often at the expense of the classic crowd.

I’ve been taking a middle road, using the approach that music theory is great, but it’s possible to lose the purpose in the theory. So, I’m conveying the idea that your personal knowledge of music theory is best utilized in interacting with other musicians that you’re playing music with and that especially includes your guitar instructor. Once you start speaking the “language” of music with teachers, mentors, band mates, peeps you jam with, all of your efforts begin to become easier, insights and “aha!!!” moments become more frequent and your skills start to shine.

Not everyone learns by reading about things, some people are more visual, some more tactile, some need to absorb everything, then learn by doing things, even if that means a lot of trial and error. Each approach is equally valid as long as it gets you to the goal of meaningfully communicating with other musicians. So my last few posts, and this one, are less about building on one another, and more about offering different approaches that work for your learning style. There will be more posts that use the concepts of music theory, but we’re going to move forward after today to practical application, and we’ll start into song structure and writing. If there are specific areas you’d like to revisit, leave me a comment - I may be able to answer, or I may ask a guest writer to post on the topics most requested.

So we’ve talked about theory, I’ve given you some visual references, today we’re going to use a variety of charts to illustrate some of those things in a structured manner.

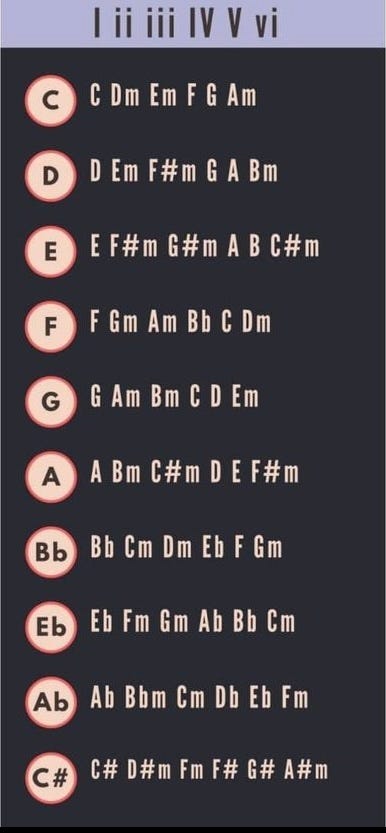

First, the chart from yesterday’s teaser had a couple of points that need clarity:

Pretty easy to read, note the Roman numerals depicting the written designation for each chord. What’s not there? No 7 chords are present - we know 7 chords are written as vii° and spoken as “seven diminished”. We’ve talked about how these chords are rarely used in modern music because we find them dissonant. Still, seems a little rude to just ignore them. If we name the chart “Commonly Used Chords in Some Keys”, we are more accurate, if still a bit rude (kinda like the decision to leave Pluto off the list of planets! Madness!!). The other point to observe is the tradition that when writing out a scale or key, we use ALL the letters designating notes. In the C# key on the chart, there is no E chord, but two F chords ( it’s like leaving Pluto out, but having two Jupiters - crazy!!). That key should be written as:

C# D#m E#m F# G# A#m and include the B#dim - note E# is actually another way of saying F, and B# is another way of saying C - but to actually follow the tradition of using every letter, we kind of use a nickname.

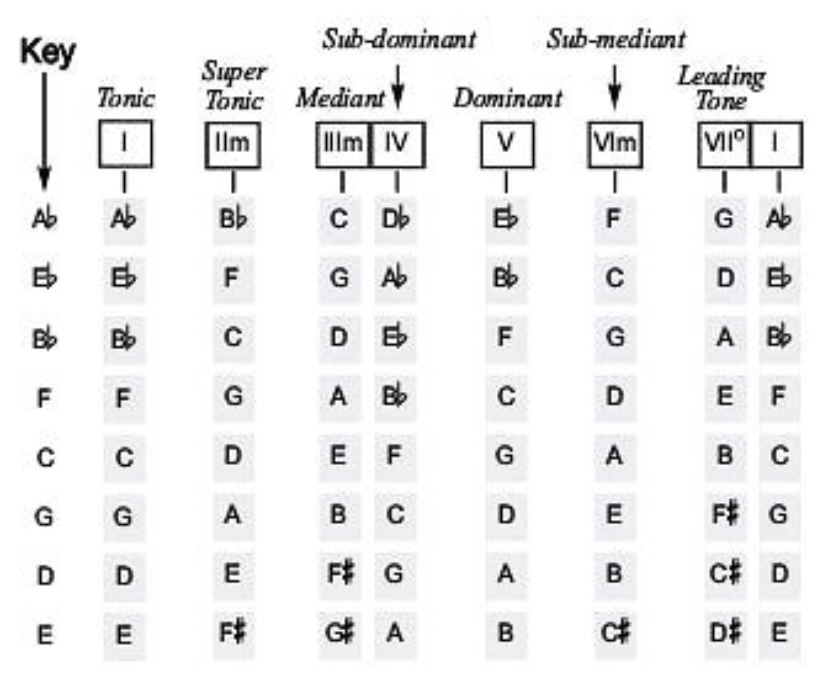

This chart gets us a little closer:

I like this chart a lot because it includes not only the vii°, but most of the classic names of each of the chord positions in the key. Tonic is the classic name for what I’ve been calling the “root”, and “Leading Tone” is another name for the classic proper name of the vii°, which is properly “Subtonic”. Note also the Roman numerals for the 6 and 7 chords should be written in lowercase: vi and vii° and the “m” is extraneous in the ii, iii, and vi.

A couple of charts that you might find handy:

This chart gives you the root, M3, and Perfect 5th (P5) of common Major chords. To make them minor chords, “Flat the 3rd”, that is diminish (flat) the middle note of the Major chord, for example, an AMaj A-C#-E, becomes an Am by changing the C# to a C, thus A-C-E. Similarly, CMaj becomes a Cm by changing the E to an Eb, and so on.

On the fretboard, this can be done pretty easily in a visual manner using this:

Note where the A-C-E notes are on strings 2,3, and 4 (1st and second frets) - the classic Am chord shape! Check out how the notes on the low E (string 6) are shown as flats (b) and on the high e (string 1) they’re shown as sharps (#). Same tones (though a few octaves apart), just written differently - I’m sure it was to save space to make the chart readable, but strictly speaking, the chart should have shown both note names, for example F#/Gb for the tone on the second fret of each E string. When you’re calculating the flat 3rd (diminished or m3) when changing a Major chord to a minor chord, keep in mind it may be written either way (b or #).

A final, maybe more practical chart:

Since we rarely play chords in their order in a key, these are some chord progressions we often find in modern, blues based music (blues, folk, country, rock, pop, Americana, just about everything, less so with jazz, though). Practice some of these progressions and listen for the very common chord progressions you may hear in popular music - chords are like the bones of a song, the melody fleshes it out - you need both!

OK, that should keep us busy until next week when we start using theory as application in songs, practicing, songwriting, and playing with other musicians. Comments and questions welcome!!

Bonus Round: the song suggested by today’s subtitle should be pretty easy to figure out, and next week I’ll show you a way to play the iconic riff by just lifting a couple of fingers (and putting them down again)!

Cheers, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic