Signature, please

How to save yourself….

Yesterday’s Bonus Round: Several good guesses, but not quite acoustic enough! Aviator’s “Song Of The Abyss” was included in and may have been written for, a video game called “Dark Souls”. The lyrics are, appropriately to the game’s theme, dark and disturbing, but the acoustic accompaniment (probably acoustic guitar and piano - but maybe all synth) are really cool - it’s on Chordify, and easy to play capoed on 2. Here’s the YouTube:

Today, we’ll begin with taking a look at “signatures” - the information in the symbols at the beginning of a music score. I used the plural because there are several. Here’s the signature for Iris Dement’s “Let The Mystery Be” in the original key (FMaj):

Starting on the left, we see the Treble Clef symbol, meaning the notation is written in that “clef”, a marker of where we are in the possible range of “clefs” - there are several, depending on the pitch of the octaves the composer used for a variety of instruments. This is handy for orchestras or ensembles playing a range of instruments or singing in a particular vocal range, from baritone to soprano. The treble clef range is sort of in the middle, and most of the notes a common 6 string acoustic guitar produces fall in this range. This is not particularly important for guitarists who don’t play with an orchestra or ensemble, but bass guitarists will often see notation in the bass clef, which looks like this:

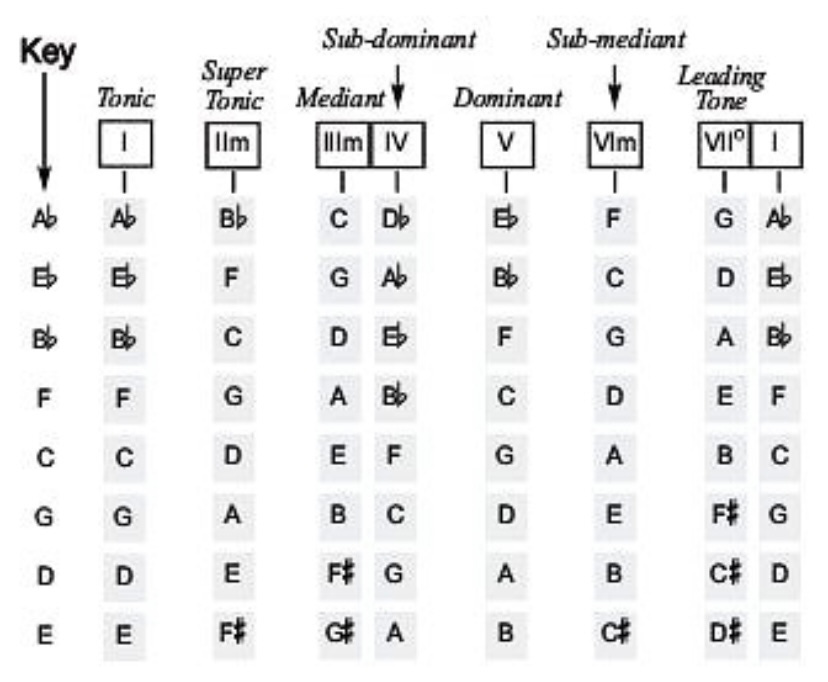

Moving on in the signature then, to the right of the treble clef symbol, we find the key signature - in this case, a single flat (b) positioned on the middle line of the score. That tells us, through some musical alchemy we’ll get to in a minute, the key the song is written in is FMaj. That allows us to understand what chords - Major, minor, and diminished - that we can expect to find in chord progressions in this song. I may have shown this before, but it’s a good reference:

In “Let The Mystery Be”, we know Ms. Dement used the I, IV, and V chords only, so by the chart we see those chords in FMaj are FMaj, BbMaj, and CMaj, respectively. It’s easily played using the I-IV-V shapes of DMaj, but we capo on 3 to do that as we discussed last week.

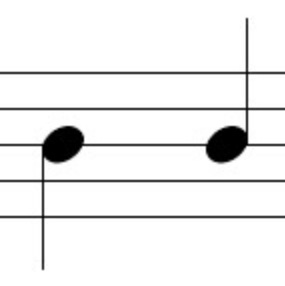

To the right of the key signature we see the time signature, here denoted as a symbol that looks like a capital “C”. It is a capital C, and stands for “Common Time”, which, in the musical world, is 4/4 time. Meaning: 4 beats to the measure (top “4”, numerator position), and a quarter note (bottom “4”, like the denominator position in math) equals one beat. Written 1/4, in notation a quarter note look like this:

In 4/4 time, it means 4 quarter note beats in a measure, and it’s the most common time signature in modern blues based music, thus the “C”, symbol in the signature. About the only other time signature you’ll ever see in modern music is 6/8 timing (6 beats to the measure, 1/8 [eighth note] gets the beat, or sometimes it’s half brother (music joke) 3/4 time (3 beats to the measure, quarter note gets the beat).

3/4 time is “waltz” timing and has the familiar 1-2-3, 1-2-3 feel. 6/8 time is sorta like that but the 1 and the 4 are usually emphasized more, resulting in a “ONE, two, three, FOUR, five, six” feel - very fun to play!!

Finally, we see a quarter note symbol, an equal sign and a number (here, 158). That’s tempo information. Since it’s written in common, 4/4 time, the quarter note gets the beat, and the number equals the Beats Per Minute (BPM). 158 BPM means 158 quarter notes played in a minute, and that’s a pretty fast tempo. Most songs range from 65 BPM (slow song) to around 165-175 BPM (really rockin’!!). At a slow tempo, you’re probably not playing a lot of 1/4 notes, more half or whole notes - 2 or 1 strums per measure. At a high tempo, you’re probably playing a lot of 1/8 or 1/16 note combinations - 8 or 16 strums per measure, and that’s fast and difficult to do dynamically, meaning you’re producing more sound, less nuance.

Last thing: that F you see below the tempo is the first chord played in this song’s first measure and it’s a clue as to the key. Most (but not all) songs in modern music start off with the root of the key it’s written in. That may not hold true for an instrumental intro, but the first lyric sung is usually accompanied by the root chord of the key.

I know that’s a lot to take in for one day, so we’ll get to the promised lyrical analysis of the chorus of “Let The Mystery Be” next week. I think today’s post is really important if you play off of tabs or chord charts in the Ultimate Guitar app or the chord progressions in the Chordify app. Ultimate Guitar chord charts often don’t include signature information, so if you submit covers or your own music there, be kind and note the Key, Time and Tempo signatures. For this song, I would write in the header info, “Key of FMaj, 4/4, 158BPM, Capo on 3” - then I would write the chord symbols above the lyrics where I perceive the chord changes to be as D, G, and A instead of the F, Bb and C of the original key. Pretty shorthand header info, but now when you see it, you’ll know what it means.

In Chordify, you can see the chords in their original key, but you can click the capo button and position the capo on the guitar neck diagram to see a portion of the new chord progression, and capo accordingly on your own guitar to play those chords. Keep in mind, you’re playing in the same key, just with different (easier) chord shapes. You can also see signature info in Chordify by selecting “View PDF” from the 3 dot menu in the upper right corner (true in iOS, not sure about the Android version of the app) - it will give you a score sheet type chord chart (but without lyrics) with signature info at the start. When you select View PDF after you change the capo position in the app, it will display a new key signature, but that’s essentially meaningless because you’ve really only changed chord shapes, not the original key itself.

If you actually wanted to play and sing “Let The Mystery Be” in DMaj because it fits your vocal range better, leave the capo off and play the D, G, A progressions. Now you’ve “transposed” the original key (FMaj) to a new key (DMaj). Just remember if you play and sing along with Ms. Dement’s YouTube video of the song, you’re literally “off key” and one of you will sound really bad.

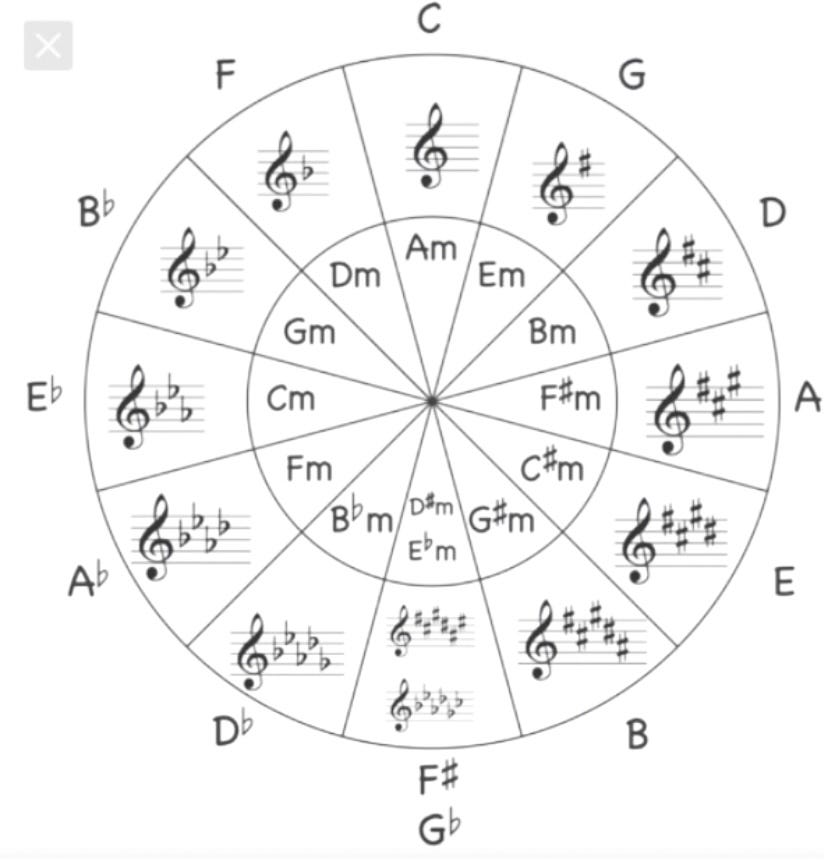

I will leave you with the promised magical music decoder ring to ponder. It’s a little like the abyss from Nietzsche‘s quote: “Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster... for when you gaze long into the abyss. The abyss gazes also into you.”, because it is both extraordinarily simple, yet hideously complex. Seriously, there are lots of actual books written about this thing, but it can be really useful in a simple way. Just don’t gaze too long…

We’ll talk more about how to use this and stay sane next week along with lyrical analysis and a very fundamental, counting.

Bonus Round: A song, not particularly acoustic this time, that starts off with a fundamental thing: Step One, and it will “save” you lots of times when playing with others. (Hint: How would you count with that piano intro?)

Cheers, and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic