Last week’s rando lyrics: “Life During Wartime”, Talking Heads, Track 5 on Fear of Music, 1979 - Hat tip to Mr. Kevin Alexander

Welcome to the Regular Friday Post! Alternate subtitle: “I’ll take Modal Thingy for a billion, ‘Jeopardy Host’!” (RIP, Alex…)

For today, let’s imagine we’ve received a package, a box, from our “odd” relative - we may have several that fit that description, but this is from, well, you know: that one…

So, it’s a bit of a “Mystery Box”; the one you stuck unopened in a dark corner. Might be something cool, might be a plastic bag containing unwashed laundry. You Don’t Know!!

But today we’re opening the Mystery Box! And in it we’re going to find: “Modes”! Hat tip to our friend and (so far, anyway) unindicted co-conspirator:

For the last couple of weeks we’ve stumbled into the “Music Theory” mystery box, and we found some interesting stuff: A note turns into a scale when you add enough other notes according to the scale formula. When you add one more than enough notes in the right order, scales turn into octaves. Scale notes turn into chords when you stack other notes according to a formula on top of them. A bunch of chords of different flavors in the right order turn a scale into a key. If you put to use the notes from a scale or the chords from a key that belong there, you’re so very, very Diatonic. Stray outside the Diatonic fenceline, and you might be an even cooler thing: non Diatonic, but possibly very uncool if you do that part wrong.

Today, we’ll open yet another nested Matryoshka Doll and see how we can take each note in a given scale, then sorta convert those notes into roots (or tonics) of scales of their own, but now they’re altered scales (with funny names!) because we change the flavor of some of the resulting scale notes along the way and call the resulting mess “modes”. Buckle up, buttercup!

But first! I promise we’re going to get back to the playing part of The Regular Friday Post soon. If you can get through the music theory portion of our program, I’m kinda hoping some of it will seep unbidden into your playing. Sorta like a dubious substance purchased from some shady looking dude on a street corner, I suppose. (Just joking! And never do this at home, kids! I just heard about it once from that one guy in junior high whose dad had a stack of hidden and unwholesome magazines. Definitely a story for NEVER…!)

Okay, modes. There’s a reason I’ve avoided modes on here. They’re difficult to wrap my head around, but let’s give them (and peace!) a chance, as they say…

So, modes are a way of taking a particular (your choice!) scale, built on any one of the 12 notes in Western music, and then building a new and different scale off each note in the original scale you chose, by using a slightly different formula for the new scales built off of each successive note of that original scale we started with. (Ed. I think….)

Yeah. We’ll get to the “But Michael, why would I ever want to do that?” question in a bit…

I’m going to link to a couple of articles that attempt to explain scale modes. I’ve read both of them through at least twice, and I’m so ecstatically happy I did, for one extremely important and fabulous reason:

They validate damn near everything I’ve written on here so far about music theory!

Yay, me! But, to get past my personal smug, I can say I learned more than I knew before about modes, which wasn’t much at all, but now I know more of it.

To begin, please, please, please - read both of the linked articles just below. You’re going to get a lot more out of them than I could bluff my way through (Ed. Though I’ve become pretty freakin’ awesome at that!) by writing about it myself.

Just one thing to remember as you work through this today: “Scales, not Keys”. The articles below may use the phrase “Key Signatures”, and both Scales (notes only) and Keys (using chords built from scales) are identifiable via the key signature, but for today we’re staying in the scale lane.

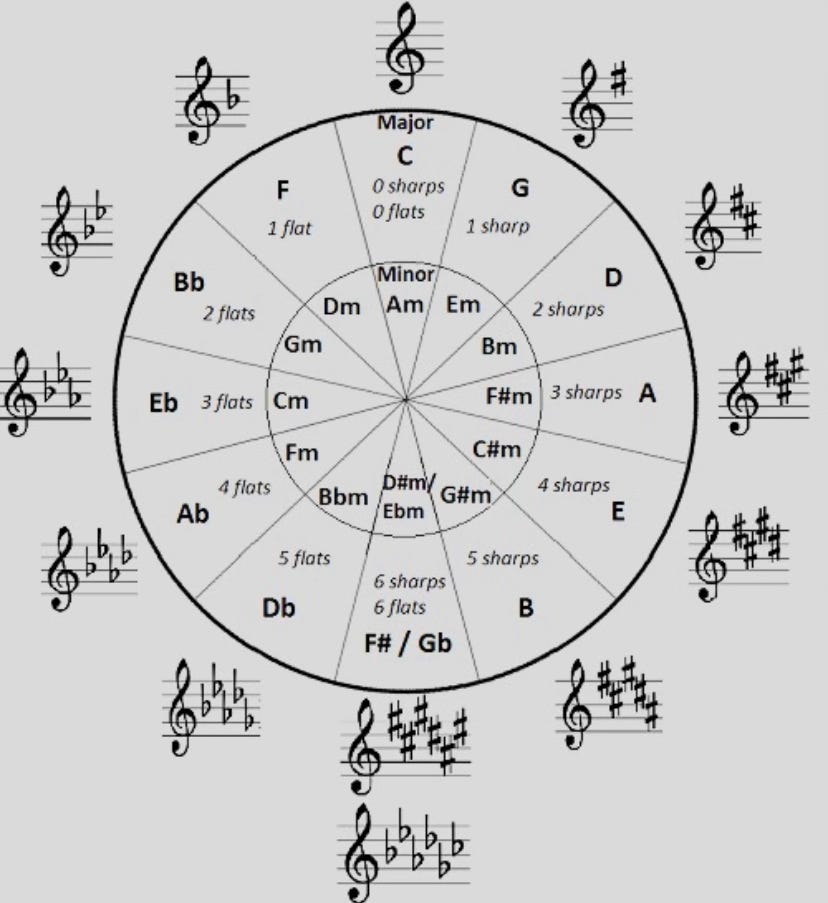

There is a way you can see “key signatures” outside their native habitat. Sure, they’re out in the wild everywhere in sheet music. But if you want to see captured little specimens pinned on the staff lines of a short little score with the treble clef along with (if it’s not “C”) some sharp or flat symbols which denote scales or keys, the Circle of Fifths is like a night in a musical freak show museum. It’s just a bit further down the page if you dare, and it is it’s own enigma: 12 notes, from which come 12 Major Scales (which, if you know the formula, you can figure out by reading it, but that’s a bit tricky) which we could use (but not today!) to build 12 Major keys or 12 relative minor (and other) keys.

This is where the Circle of Fifths can be an annoyingly all too clever little beast. The 12 letter notes around the outer circle can be the tonics of Scales, or roots of Keys. The 12 inner circle letter combinations explicitly reference chords in a Key. Remember in a scale we can have natural notes and sharp/flat accidental notes (except “C”, again…) - but the Major, minor, and diminished designations only apply to chords within a Key. So, to read the inner circle as notes, instead of chords, you have to mentally ignore the lower case “m”. By doing that, they sort of magically transform back into notes. I’ll tell you how to use the Circle of Fifths to figure out the chords in a key, or by ignoring the lower case “m”, the notes in a scale next week, cuz I’m pretty sure we’re all out of that sort of mental contortion energy by now…

Except, and this is really freaky, after emphasizing for today how modes are scales, next week I’ll warp this whole thing further by showing how they can become keys. (Ed. Just ignore that sentence for a week…..)

To reiterate (again, cuz it’s important) the 12 Key signatures themselves are often found out in the wilds of sheet music scores and can tell you which Scale (or Key: Major or the relative minor), the piece is written in. That’s handy, but the real meat is the letters and stuff inside that outer ring of key signatures. This image happens to be the wallpaper on my phone - yep, it’s that handy (and confusing)...we’ll peer behind this veil of shadows next week…

Read me first!! Link> How Modes Work (Ed. OK, this is a bit more chordal than scalar, and it’s not as thorough or fixated as I am about distinguishing the two, but it’s pretty good, so..)

Did you read it? Lots to unpack there. If you’ve been playing for awhile, you’re likely familiar with the pentatonic “boxes” scale diagrams. If not, that’s fine. Below is an example from the article, but it’s not a Pentatonic Scale box, it’s a diagram of notes (copied and pasted from the article above) from one of the “modes” of the F Major scale, in this case the first one, Ionian, which coincidentally is also the F Major scale. In modes lingo, you could call it by it’s “mode name”, spoken as “F Ionian”, instead of, or in addition to, its more common name, “The F Major Scale”. I’m talking about the scale using F as the tonic as the “example” scale here, because that’s what the article uses, but there are 11 others to choose from…have fun….

You can first play it from the top (first fret), left to right across the fretboard, then the next fret down (second fret, left to right) and so on to get the “feel” of the scale. (Piano players, do your own thing…) The “open” (not filled in) finger placement dots are the tonic note “F”, the solid dots are other notes from the scale. After a run through (suggested, but your call) you can experiment by playing any or all of the notes in whatever order you like, they’re all Diatonic to the scale, but that doesn’t mean every sequence will sound “good” - have fun, and there are diagrams in the article for each of the other modes - playing them may be more enlightening than just reading the article or looking at diagrams:

So, big takeaway, (emphasized above as well) but kinda important. For today: “Modes” are just scales, not keys. Get that concept down first. Say it with me, “For today, they’re just scales!” Two of them are probably familiar. The “Ionian” mode is just the Major scale of whatever note is the root. The “Aeolian” mode is just the “natural/relative minor” scale of whatever note is the tonic.

So maybe it’s good to first think in terms of a “base” scale. Pick one, there are 12, seven of those have Natural notes as the root (aka “tonic”), and 5 of them have Accidental notes as the tonic (aka “root”) - see what I did there? Two different words for the same concept! Amazing, though I suppose “tonic” is more accurate for scales, and “root” is more accurate for keys. We’ll talk a bit more about that next week. Maybe.

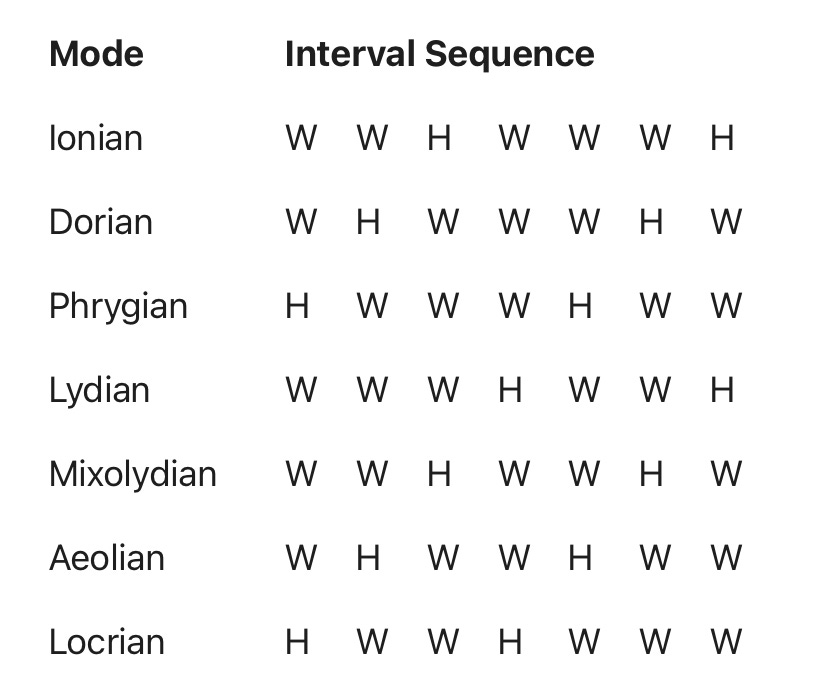

Just pick a note - it’s probably easiest to just use a Major scale which has the interval formula: “WWHWWWH” where W equals a whole step, and H equals a half step (thus: whole, whole, half, whole, whole,whole, half), and then if you don’t have a chart, construct it yourself. If you’re in a mood, use a minor scale interval formula: WHWWHWW (whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole). Notice how you can use part of a Major scale pattern to create a minor scale by just starting on the 6th step of the Major scale, and when you get past the 2 intervals (the sixth to the seventh, and the seventh to the octave) that are left just add in the 5 intervals from the beginning of the Major scale. If you can wrap your head around that, you can sort of see why the Ionian mode has a relationship to the Aeolian mode, and maybe that helps to see how all the others relate as well.

But that reveals a more basic truth about modes. It’s this: They’re really about the intervals between notes, rather than the particular notes of a scale themselves. Even if you get just a little of anything else here - keep that in mind. Yeah, it’s scales, but the pattern of intervals is more important to understand because you can change out “base” scales, thereby changing the sequence of notes, but you’re stuck with the same sequence of interval changes regardless.

To paraphrase unreversed ELO: “The notes are interchangeable, but the intervals are not. Turn back! Turn back! Turn back! Turn Back”

Let’s see if the next article can help us:

Read Me Next!! > Musical Modes Explained (Ed.This one is a bit friendlier…)

I think this helps a lot:

See the pattern? The first interval, “W” (whole) or “H” (half), of each mode“drops off”, and becomes the last interval of the next mode below, sort of “pushing” the other intervals to the left as we progress downwards. When that pattern is repeated 7 times, we run out of modes. Why? 7 notes in a scale, 7 intervals (though the final interval takes you to the octave - that’s why we need the octave), 7 different modes, and some notes in your chosen “base scale” can change in each successive mode. It’s handy to understand that the “order” of intervals all change relative to the previous mode by one interval (which can, but not always, have the effect of changing a natural note to an accidental and vice versa), and once you reach the bottom of the chart above, if you just stacked another identical “modes chart” below the one above, it would be repeated using the same 7 notes from your chosen base scale, and the result would be modes, like turtles, all the way down…

But that’s the “trick”: Each mode is “changed” from the previous mode a little when the Whole step, half step interval pattern changes. Again, meaning flat accidental notes may begin to appear where there were only natural notes before, and vice versa.

Why? What’s the point of “modes”, anyway? This paragraph from the first article gives us a hint:

“Each mode was said to convey a particular emotion or effect, but their exact meanings were lost due to philosopher Manlius Boenthius’ mistranslation of an important text circa 510. Consequently, the names of the modes were reassigned to the seven degrees of the major scale, and most of their history and original function disregarded."

Note the funny names of modes derive from the names of ancient Greek places, sorta.

From an unusually cogent Reddit conversation I found:

“To understand this you first need to understand a little bit of Ancient Greek music history. The Ancient Greek music varied from culture to culture within Greece, and certain tunings were associated certain areas (this is kind of similar to how there is a "chicago" blues, a "new orleans" blues, etc). Thus the Ancient Greek tone collection from Phrygia (the same Phrygia mentioned in the Iliad) would use what became known as the “Phrygian" collection of tones”. I should note that these are not the modes as we think of them in the modern sense; The Greek Lydian “mode" would sound nothing like our modern lydian mode. The modes came to us because Medieval Musicians thought it would be cool to name their scales off of Ancient Greek Music (regardless of how close the sound actually was). We in turn got the name of our modes from this music, though now, due to the rise of equal tempered tuning (among other things), our modes sound nothing like the church modes or the greek ones. But that is where the name comes from.”

So don’t get hung up on the Greek place names of modes - despite the names, they don’t relate to the actual musical history of Greece, which is mostly unknown. Maybe they’re an apologetic nod to the “lost by mistranslation” history of music in ancient Greece. Maybe they’re just nostalgia, dunno. In reality, the modes could have been named for places Bilbo or Frodo visited and had as much musical relationship to what we now call “modes”. Though kindly Professor Tolkien may have had a conversation with his Intellectual Property attorney about that.

In the second article, the description of each mode gives us a modern view of what emotions may be invoked as we work in the different modes, but we still can’t know the intentions of the original musicians who used them centuries ago. Those intentions are lost to antiquity, but the modern listener can still be influenced by hearing the changes in the patterns of flatted and unflatted notes from what is “expected” from the more familiar scales.

Some of them may be “happier”, more upbeat to our ears, others more downbeat and “sad”. Why? In the end it’s most likely because we hear the unexpected intervals that occur in some of the modes. They’re unexpected because we’re used to hearing music in Major and minor scales, not realizing or caring that each of those are actually “modes” as well. The other five modes we’re looking at are where we hear the interesting and unusual altered interval sounds.

Gotta say, “I don’t particularly like modes a lot.” Sure would be handy if there was a mnemonic for the modes order, though: Musical Mnemonics

Next week we’ll contradict a bunch of stuff from today’s post and build keys from the scale modes. It’ll be like a visit to the “Forbidden Planet” (Janet-sssss) but without Anne Francis or Leslie Nielson or the other guy….

New Space Saving Disclaimer!: This Substack, (not just the first one!) is free, always will be, none of the people or companies or products I link to or write about pay me a damn thing. Neither do you unless you buy my song(s) (See what I did there?). Some stuff may be copyrighted by somebody else…whatever. “Fair Use” doctrine for “educational purposes” (Link: Fair Use) applies, suckers! No stinkin’ AI here unless it’s in something I link to. So.

Michael Acoustic

Thanks new Subscribers!!!!!! Mika, the Cat, welcomes you!!

This Week’s Conversation With “Angry Cat” Mika:

Me: (laughing) Your legs went straight out in four directions when I picked you up just as you were about to go after that little bunny!

Mika: I would have protected us both from that monster if you wouldn’t have interfered!!

Me: (Laughing intensifies..)

Special Edition Of Odds/Ends

A reader commented on yesterday’s subject of lyrics that convey emotions, and mentioned how much emotion was evident in the lyrics to Alanis Morisette’s song “That I Would Be Good”. Absolutely true, and I’m pleased to include some of the backstory to the song here, as well as the MTV Unplugged YouTube video. The emotions come through in the lyrics and Ms. Morissette’s stunning vocals:

"That I Would Be Good" is a song by Canadian singer-songwriter Alanis Morissette that was first included on her fourth studio album, Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie (1998). An acoustic live version of the song was recorded during a session for MTV Unplugged on September 18, 1999.

The lyrics relate Morissette's intimate feelings about being judged, insecurity and self-doubt, expressing in theme and variation the desire to be sufficient in the face of changing external circumstances.

Lyrically, "That I Would Be Good" claims a self-confidence independent of fluctuations in emotional state or physical appearance.[11] It is filled with wonder over whether one still feels whole in the face of any number of life's ills: losing youth, bankruptcy, insanity, the absence of a chosen lover.[6] ……the song was written during a time when there were many people in her house and she retreated to her closet to write the lyrics. She also confirmed that she wrote the lyrics and then the music at different times.” Credit Wikipedia Link: That I Would Be Good

Shameless self promotion section

My song is out! “Long Road Back” (click on link for streaming options)

What I’m Listening2: Just one today, but it made me laugh!!! The Intelligence Community has it’s “6 Ways To Sunday”, but that’s nothing compared to the Actual Malice of pissed off musicians. This was a while ago, but good luck, Public Figures, the truth is a complete defense to defamation…. Link: United Breaks Guitars

https://twitter.com/historyinmemes/status/1687531582125441045

Even Taylor Guitars weighed in:

https://twitter.com/amirmushich/status/1687549433360109569

Cheers and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic

“It’s never really final - you just run out of things you can bear to change…”

Thanks for bringing back “That I Would Be Good”, an all times favorite of Alanis and probably one of the seeds of what Reflect & Relax Cafe is today.

Aaargh! Very hard to get my head around it. I’m sure you’re further along. Here are some questions I’ve never been able to get my head around.

Am I using all the regular chords and harmonies and just soloing with the modality on top of them? In other words am I playing a I-IV-V, but just doing something with a Lydian scale on top of those natural chords and leading the chips, fall where they may? Or am I actually changing the underlying harmonies to match the modality in other words are they cooperating with each other?

Or is the tension that they’re using different notes in the first place? Am I using Mixolydian because I was going to play a C7 in the first place? Are they otherwise just descriptions for the harmony you’ve already chosen to play?

As I move a new chord in the sequence am I also changing modalities per chord. This is a variation of the previous. For example, would I play an Ionian over the 6th creating all kinds of harmonic soup?

Or is the point somehow that you build a melody with the idea of the first tone being “home” is it where the melody naturally resolves itself?

Or is the idea that it breaks with a scale all together, and every chord brings along its own modality baked in?

I get how they are constructed but not how they are related to the underlying chords.

It’s not you. It’s me.