Other Voices:

Thanks to Steve Goldberg of the Earworms and Song Loops Substack for today’s Rando Lyrics, which definitely turned into an earworm, defeated only by the surefire method of singing “Don’t Fear The Reaper” in my head until the magical cleansing properties of Blue Öyster Cult (it’s the umlaut that does it, folks….) worked their healing power.

Last week’s rando lyrics: The lyric, “I even like the chicken if the sauce is not too blue”, is from the song “TV Dinners” which is Track 3 on Side 2 of ZZ Top’s March 1983 album “Eliminator” released on the Warner Bros. Records label, and produced by Billy Mack Ham. The song was co-written by the members of ZZ Top: Billy Gibbons, Dusty Hill, and Frank Beard and released as a single in December 1983. Credit: Wikipedia Links: TV Dinners. Eliminator

Welcome to The Regular Friday post!

For Today:

So, it’s that time of year, Christmas and New Year’s has come and gone, it’s back to work and today’s post is no exception. Today, I’ll understand if you skip to the picture of Mika, The Cat, or to the playlist or wherever, but: This Has To Be Done!

Yes, it’s the biennial Music Theory post!!

So, I’m just going to rip the bandaid off and go with it:

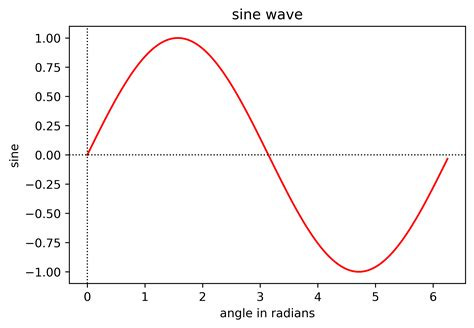

Everything starts with a note. A “note” is a sound that the human ear “might” be able to hear because our ears have evolved to translate certain vibrations in the ambient atmosphere as a “note”. Some of us are better at that than others. Newborn babies are thought to be able to hear sounds that vibrate the ambient atmosphere at frequencies we denote in a measurement known as “Hertz” (named for the guy who detailed how that works) - from ~20Hz to ~20 thousand Hertz (20KHz). Babies begin to lose the ability to hear a range of frequencies that broad almost immediately and by the time we’ve reached our late teens or 20s the range is much smaller. A “frequency” is determined by the number of “sine” waves that occur in a given amount of time. We conceptualize the appearance of a sine wave as:

“A440 (also known as Stuttgart pitch[1]) is the musical pitch corresponding to an audio frequency of 440 Hz, which serves as a tuning standard for the musical note of A above middle C, or A4 in scientific pitch notation."

“The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second.” Credit: Wikipedia Links: A440 pitch, Hertz

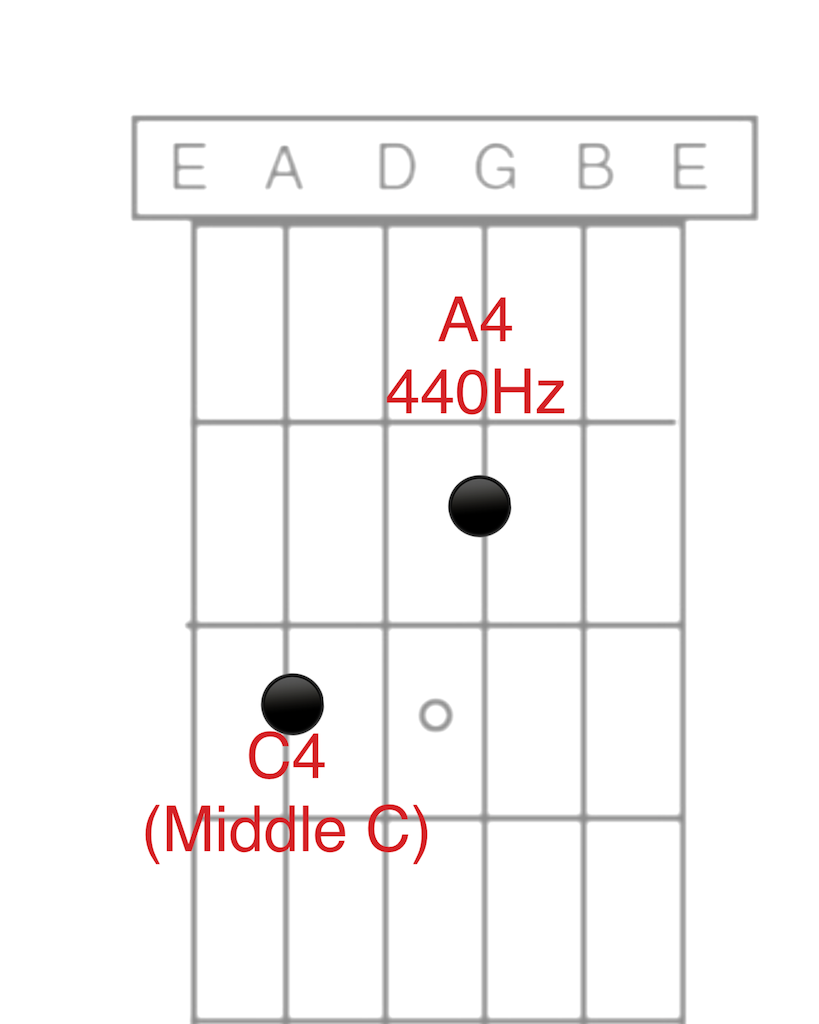

So a properly tuned guitar, with all other strings muted will produce 440 sine waves in a second when the G string is fretted at the second fret and plucked once.

C4 (Middle C) and A4 (440Hz) on a guitar:

A440, or A4 on a piano, or second fret on the G string (and at least one other place) on a guitar is the “reference” frequency for every other frequency within the possible audible range for human beings. Ed. Note “C4” means the C note in the 4th octave from the left end of an 88 key piano keyboard. A4 is the A note pitched to the right on the keyboard of C4.

Great, so what? It means your Snark (or whatever brand of tuner you use) will recognize every note you play on your guitar fretboard with reference to A4 at 440 Hz. Every other note will, if your guitar is properly tuned, will be some standardized frequency above or below A4/440Hz. Magic!

Well, sorta - more like science, but let’s go with magic for now. What does it all have to do with music theory?

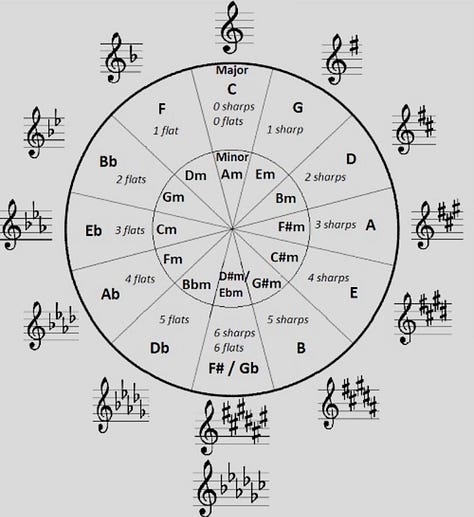

It’s a place to start. Like a note - pick one, there are 12, and we’ll make a scale out of seven of them. We have Natural notes we can use as the root (aka “tonic”), and we have Accidental notes we can use as the tonic (aka “root”) - see what I did there? Two different words for the same concept! Amazing, though I suppose “tonic” is more accurate for scales, and “root” is more accurate for keys. We’ll talk a bit more about that. Maybe.

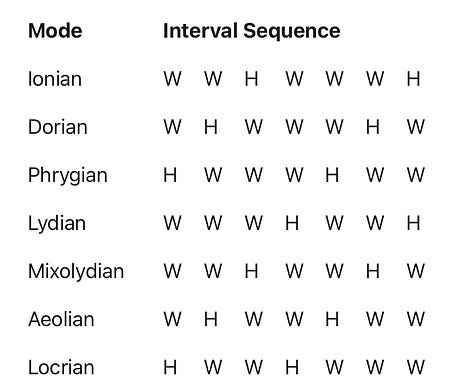

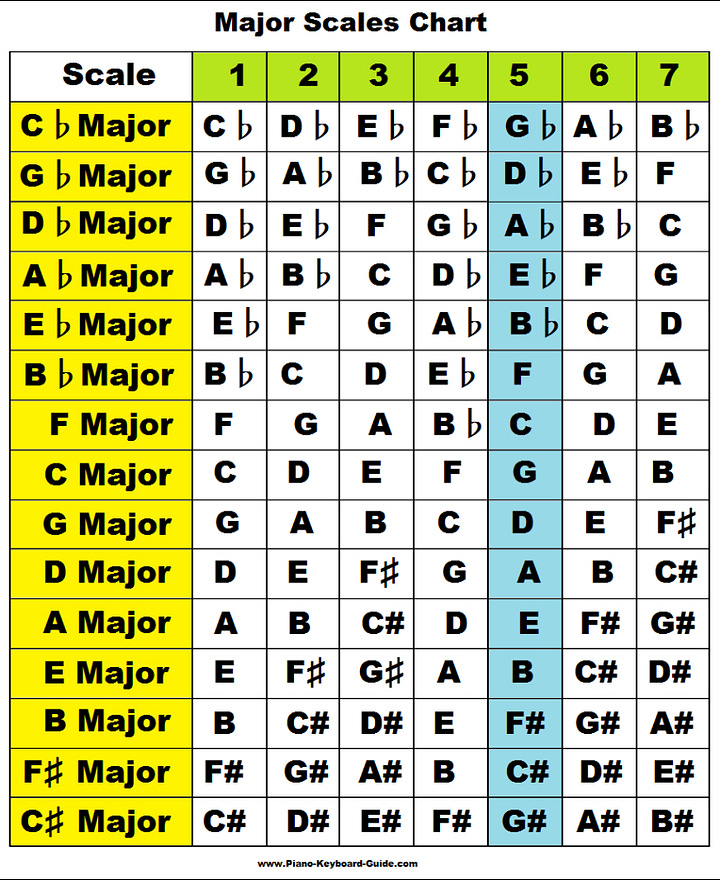

So you picked a note to build a scale from - for today, it’s probably easiest to just use a Major scale which has the interval formula: “WWHWWWH” where W equals a whole step, and H equals a half step (thus: whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half), and then if you don’t have a chart, construct it yourself. If you’re in a mood, use a minor scale interval formula: WHWWHWW (whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole). Notice how you can use part of a Major scale pattern to create a minor scale by just starting on the 6th step of the Major scale, and when you get past the 2 intervals (the sixth to the seventh, and the seventh to the octave) that are left just add in the 5 intervals from the beginning of the Major scale.

There are lots of other places to start, but in scales that are ordered properly (“properly” here means “according to the rules”, which you can break anytime you feel like it if it still sounds “good”, whatever that is) in one of several types of “scales”, we start with the first note of that scale. You can start with any note you want, but in Western music there are only 12 notes so we have to pick one of those. Music in other parts of the world may have more, less or different notes than “Western” music (i.e., European, or at least non-Asian, music that “started” there and then migrated to the Western hemisphere…yes political purists, I recognize the word “Western” refers to Greco-Roman tradition, doesn’t change the fact that it migrated to the “Western” hemisphere, though). A scale starts with one of these notes and proceeds from there. The note that starts the scale is called the “tonic”, though we often call it the “root” note as well, because it’s the name the scale is called. Thus a “C scale” starts on the note C. From there, it depends on the type of scale we either want, or that we’re faced with. We “want” a scale when we’re writing or creating music, we’re “faced with” a scale when someone else has created music we’re going to play.

Let’s assume we want a “Major” scale. Great!! We have the formula for that! It’s the one from a couple paragraphs above. and let’s explore the W’s and H’s. To understand the the formula, we have to understand “steps”. There are 2 types of “steps”: Whole steps and Half steps. 2 half steps equal a whole step. Let’s think of a piano keyboard for a moment.

So - if you started with the C on the left end of the diagram, played only the white keys and stopped before you played the C at the right end of the diagram, you would have played the notes in order: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and that’s the CMajor scale. That’s 7 notes and there are 7 notes in Major and minor scales. You would also have played a Major scale because the pattern of W’s and H’s (meaning Whole and Half) as shown in the diagram is the pattern for a Major Scale. The Major scale pattern for CMajor is unique. It’s ends up played only on each successive white key, with no black keys played. But do count the keys, white and black keys from the C on the left end through the B on the right end (stop counting before the C key on the right end). That’s twelve notes. The twelve notes in Western music. The seven white keys (CDEFGAB) sound what are called the “natural” notes. The five black keys sound what are called the “accidental” notes. I don’t remember the reason for that from my music theory classes, let’s just go with it. The Natural notes have only one name. The accidentals get two names: See the black key between the C and the D at the left end? That’s C#. Or Db. Or C#/Db. By convention, if you’re going from left to right, you name the black key with reference to the white key to the left. So in the scale above the key between the C and the D would be C#. If you’re going right to left, the black key between would be Db. What if you’re not doing either?

Yeah, dunno how, but some names just seem to stick. It’s usually Db, but sometimes C#, and almost always Eb instead of D#. There’s no accidental between E and F, so no name. Between F and G is almost always F#, but between G and A is almost always Ab, and between A and B is almost always Bb. No accidental between B and C, so no name (generally - but unless the person is a well known composer, don’t let them get away with B#/Cb or E#/Fb - there’s no such thing, but there have been cruel composers who wrote sheet music like that anyway).

Back to our little CMajor scale above for a second: Pentatonic, Blues, chromatic and any other scale that’s possible could have fewer, more and/or different notes, but that one is a CMajor scale. If you didn’t stop at the B and played the C on the right end, you played an octave.

“An octave (Latin: octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason)[2] is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency.” So from A4 at 440Hz to the A note in the fifth octave is double in frequency: A5 equals 880Hz. Credit: Wikipedia Link: Octave

Okay, that’s scales. Remember, scales are notes. Seven notes to a Major or minor scale. Scales are what you use to solo on a guitar. Do you have to use the notes of a particular scale only? Nope. Later we’re going to see how scales become keys that use chords, but you can use chords from outside the key as well. Notes that are in the scale or chords that are in the key according to the formula are called Diatonic to the scale or key. If the note or chord isn’t part of the scale or key by formula, they’re called Non-Diatonic. Kinda the rule is, if it sounds good, it doesn’t matter, but some non-diatonic things sound better than others. If you don’t care, nobody else does either, though if commercial success is your goal, choose wisely when using non-diatonic elements.

The formula for a Major scale is the root note (that the scale begins on), followed by the next note a whole step higher, followed by another note a whole step higher than that, followed by a note one half-step higher than that. So far we have 4 notes, which we can also identify by scale degrees - and we call those the Tonic (root), the Supertonic (second scale degree - whole step), the Mediant (third scale degree - whole step) and the Subdominant (4th scale degree - half step). What’s left? The fifth scale degree, the Dominant, is a whole step up, the next degree, the sixth scale degree, is a whole step up and called the Submediant, and the 7th scale degree, is most often called the “Leading Tone” in Major scales and the Subtonic in minor scales (sorta - there is a reason for it, it’s because the seventh scale degree needs someplace to go and that place is the octave - a half step in the Major scale, a whole step in a minor scale and somebody thought it would be a good idea to have different names for what is conceptually, if not structurally the last interval between the Submediant at the end of the scale and the octave… I remain unconvinced, but meh).

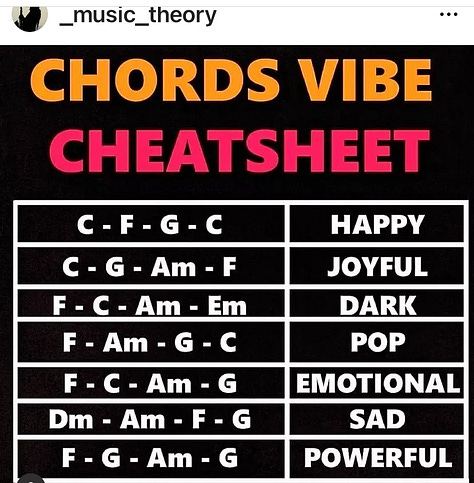

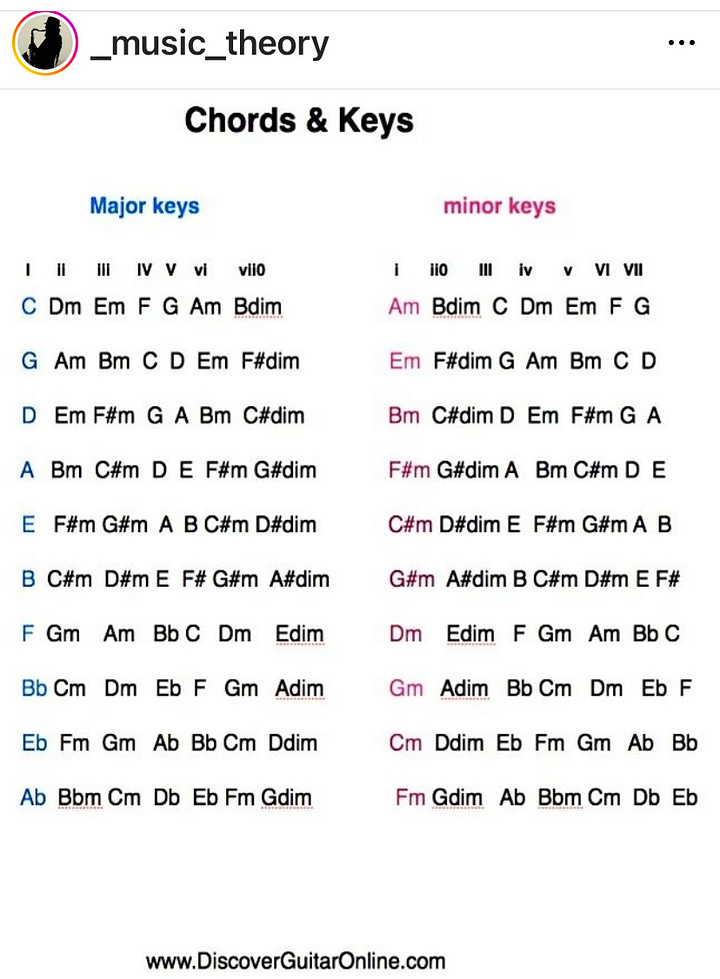

I know - if you’re still even with me, it’s a lot. I want to take a minute to briefly (as possible) explain how we make a key from a scale. Using the scale notes (and I’ll give you some pictures in the memes and stuff section for those who prefer visual reinforcement), we transform each note in a scale to the root of a chord. In the C scale above, the notes of the scale are CDEFGAB. The Chords in the Key of C have the same basic names, but they come in 3 different “flavors”, according to an additional formula (it’s this overlapping of “formulas” that makes music infinitely interesting!!). That formula for a Major key means the first, fourth and fifth chords of the key are Major, the second, third and sixth are minor, and the seventh is a completely different type of chord, the “diminished” chord. Note that while the 4th and 5th scale degrees - the IV and V chords - follow the construction of Major chords, they are called “Perfect Chords” - the reason is because each of these chords is thought to be capable of resolving well to the root. Is that really true? It is in Western music because our ears have been “trained'“ to hear a resolution to the Tonic from the Dominant (or V chord) as pleasant. It’s actually known as the “Authentic cadence” - cadence being another word in this context for “resolution”, sorta. The Subdominant (IV chord) resolution to the Tonic (root) is called the “Plagal” cadence or resolution and is almost as pleasant as the V-I authentic resolution. Plagal is a term that has religious connotations and is appropriate, since the IV-I resolution is reminiscent of the “Amen” that often ends religious choral music (try it - you’ll hear it too…).

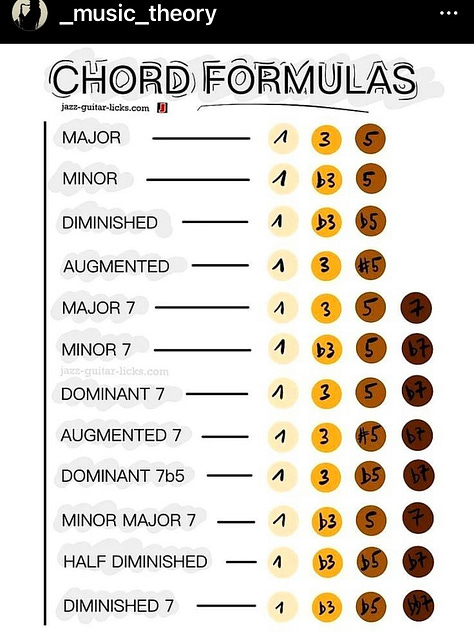

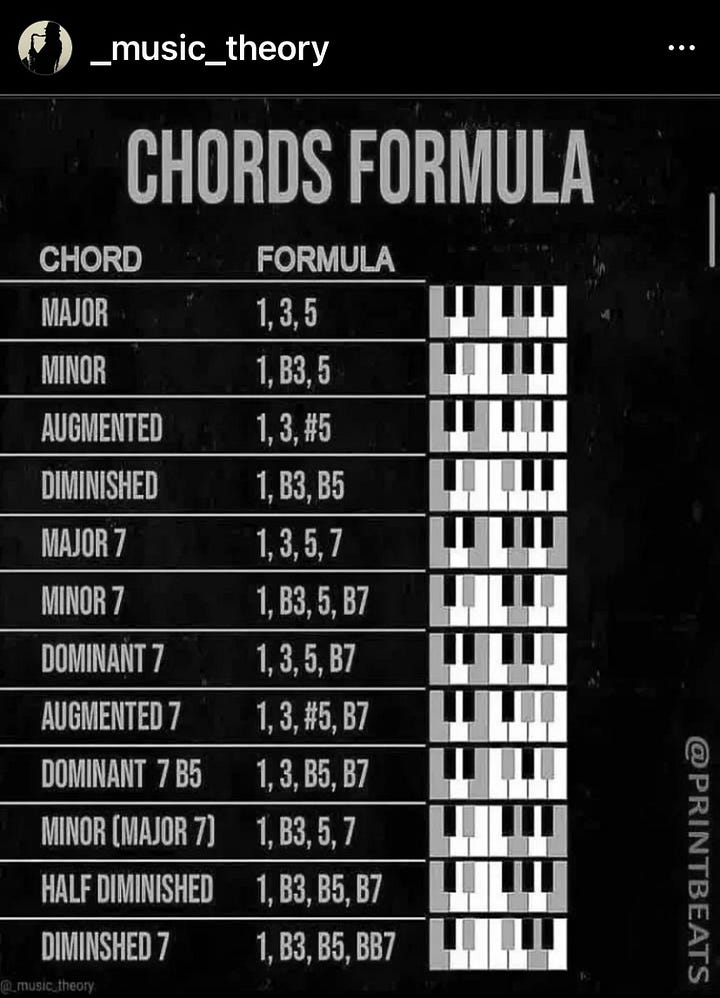

Okay - I know we’ve kind of overtaxed that wonderful part of our brain that comprehends music theory today. So, good news!! We’ll do the rest next week!! Yep, we’ll construct chords of various types (triads and sixths and sevenths, oh my!). We’ll talk about chord progressions, we’ll talk about how to write progressions over lyrics - the difference between harmonic (chordal) music and melodic (single note at a time) music. “Add” number chords, or chords with numbers but not “add” and what they mean. “Sus” chords and why they’re cool. What makes a chord Major, minor or diminished. And a bunch of other stuff, too.

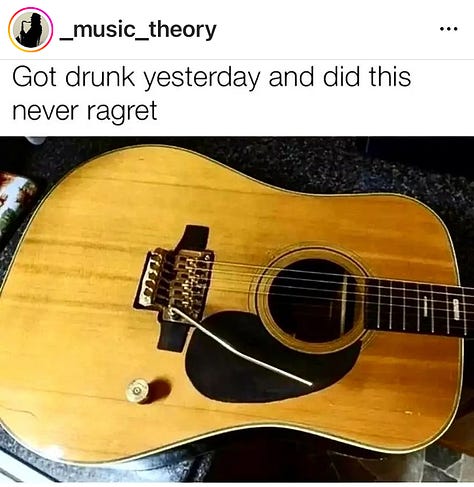

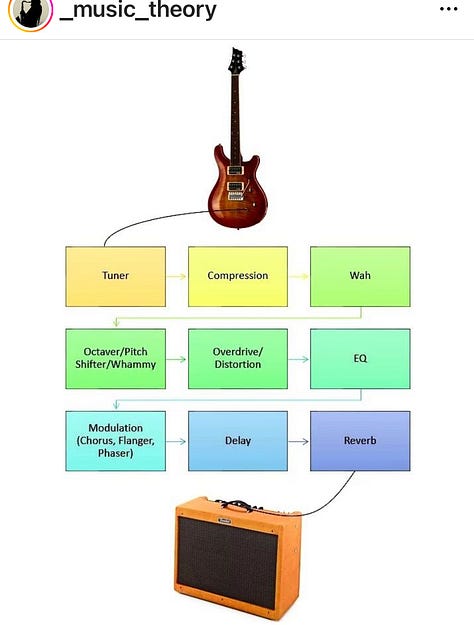

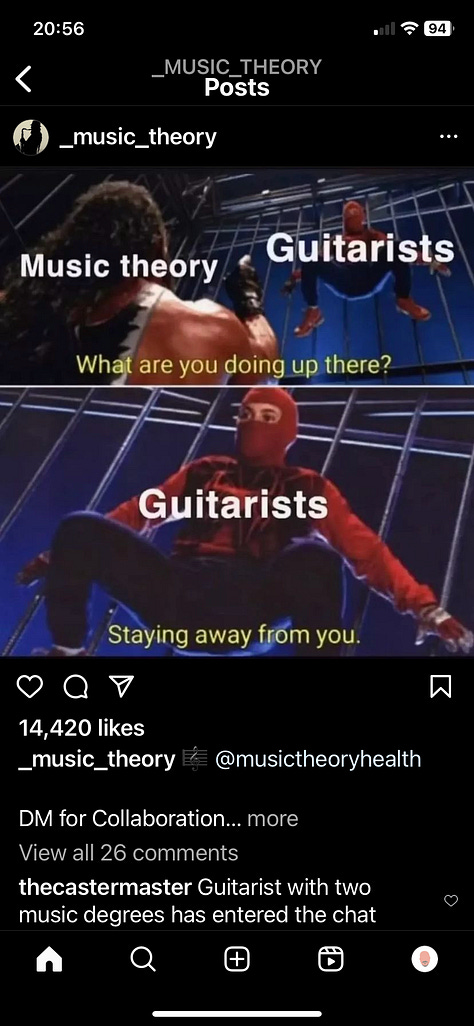

Some Memes And Stuff

Some more memes and stuff:

Thanks, New Subscribers!! This Week’s Conversation With Mika, the Cat:

Me: “What?”

Mika: “Stop talking to those people and give me treats, that’s what….”

Me: “OK”

Mika: “purrrrrrr”

This Substack is free, I receive no compensation of any kind from companies or products I mention. Some linked or quoted material may be copyrighted by others, and I credit them. I rely on the “Fair Use” doctrine for educational purposes (Link: Fair Use). I do not use AI, things I link to might though. -Michael Acoustic

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support this newsletter.

Some Links for today:

No Links today, you’ve suffered enough by staying with me this far, through all the music theory pain…

Shameless Self Promotion Section:

My song is out! Link: “Long Road Back” (click on link for streaming options)…

What I’m Listening2:

LINK»> Aminor Backing Track (Aminor is the relative minor of CMaj, so just improvise using chords from CMajor) just click the underlined link, it’s on Amazon

Cheers and keep playing!!

Michael Acoustic

“It’s never really final - you just run out of things you can bear to change…”

Interesting - I’ve not - pretty much stay with 11s, custom lights. I’ll check out the video - thanks!

The Reverend Billy F Gibbons is one of my top 5! Have you tried skinny 7 gauge strings? (cool video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEzIcX4kznY). Have a good one!